Yinka Shonibare’s Jardin d’amour [Garden of Love] (2007) was the second – and most high-profile thus far – of the single-artist installations staged during the Quai Branly museum’s early programming history[1]. The artwork consisted of a labyrinthine, reconstructed 18th century Rococo-styled ornamental French garden arranged as three secluded enclosures in which different thematic tableaux were staged.

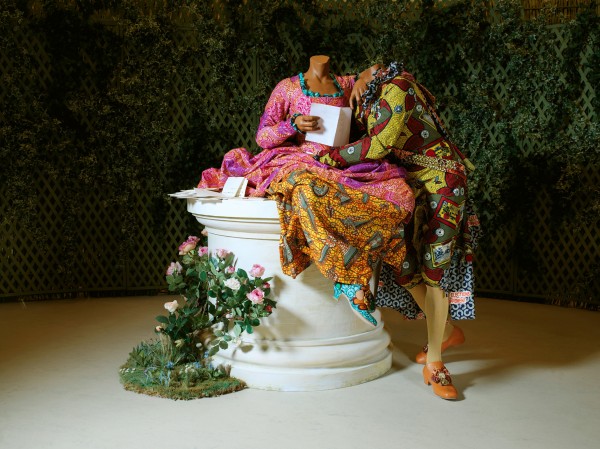

Each of the main display areas were separated by shrub-covered trellis, tightly bound reed-screen fences, privets, climbing plants and artificial rose bushes that served as foliage-covered boundary walls around the entire exhibition. The three interiors comprised groups of Shonibare’s signature life-sized headless mannequins, dressed in Dutch-waxed, patterned cotton textiles, and with beige tinted limbs, perhaps so as to make the ethnic origin of the characters they represented ambiguous and indeterminable: neither African, Asian, European, Australasian nor American in origin, but perhaps instead an intentionally hybrid representation of all humankind. From the titles given to each tableau – « La poursuite » (‘The Pursuit’), « l’amant couronné » (‘The Crowned Lover’) , and « les lettres d’amour » (‘Love Letters’) – the installation echoed and evoked the settings featured in three 18th century oil paintings by the French artist Jean Honoré Fragonard, collectively titled Les Progrès de l’amour [The Progress of Love], and painted between 1771 and 1773 (Müller, 2007b: para. 9).

The use of the brightly coloured, patterned, Dutch-waxed fabrics give Shonibare’s sculptural tableaux a different type of kinetic energy to the movement symbolised in Fragonard’s oil paintings and creates an aesthetic which several cultural theorists have interpreted as Shonibare’s signification of ‘black dandyism’ – not as featured in 18th century pictorial caricatures about African servants being dressed in ornately decorated outfits and uniforms as a show of the wealth and social status of their powerful European employers (see, for example, Dabydeen, 1987, Smalls, 2003), but rather a ‘new dandyism’ where the mimicry and signification are actually more complex articulations about capitalist relations of consumption by African and African diasporan artists who position themselves as the ones deciding how to fashion bodies placed on display, as opposed to assuming marginalised roles as objectified individuals forced to dress in a particular way by more powerful others (Miller, 2009: 221, Finerty, 2011, Badinella and Chong, 2013: 17).

If anyone’s artwork has the potential to mount a challenge to the institutionalised othering of Africa and Africans by Western museums – and, in this case, the MQB – Yinka Shonibare’s art is widely regarded as powerful enough to disturb even the most traditional and resistant organisations, as evidenced by museologists and curators such as Okwui Enwezor (Enwezor, 2001b), Thelma Golden (in conversation with Enwezor, 2001a) and Bernard Müller (Müller, 2007b). As a co-curator of Garden of Love, the academic and freelance curator Bernard Müller describes Shonibare as « un maître de l’artifice » (’a master of artifice’) who operates best in cultural spaces like MQB that are founded on the ‘illusion of otherness’ (Müller, 2007b: para. 19).

In response to the Quai Branly commission Shonibare himself felt that the scientifically ethnographic and historically colonial context of the collections was perfect for his work – particularly because it was a way for him to challenge the historical and stereotyped denials about African modernism that prevail in Western (art) historical discourses. Nevertheless, he also acknowledges the complexities of juxtaposing traditional and contemporary art forms in such a museum space:

It’s a very complicated issue. I certainly will not say, as an artist, that all ethnographic museums in Europe should be abolished. And in a way I also feel a contradiction. I don’t like the way the objects were acquired politically. Quite a number of these objects were indeed looted and as such they are symbols of conquest. But culturally, I am happy that some of the objects are there and I can see them. The question arises of course whether they are preserved in the right context or in the right way. (Yinka Shonibare, in Müller, 2007a: 20)

Sara Wajid’s review of Garden of Love for Darkmatter gives an indication of how the MQB’s commission of Shonibare’s work has been interpreted by members of the British art press, suggesting that the museum’s lack of ‘legitimacy’ was not only as a result of poor curatorial decisions made, but was actually most noticeable in the institution’s starkly unrepresentative workforce of almost exclusively middle-class white employees that is unrepresentative of the more diverse Parisian population, or the international tourist audiences visiting year on year.

This is an important point in favour of the commission; on the level of ‘branding’ it simply cannot be faulted. Take one culturally suspect institution (the interior decor has been described as ‘jungle whimsy’ and the very idea of grouping non-western collections under one roof raises the spectres of ‘exoticism’, ‘primitivism’ and ‘orientalism’). Add an ambitious commission by a painfully cool black artist with impeccable political credentials and hey presto – instant cultural legitimacy. (Wajid, 2007)[2]

Shonibare’s alternative outsider credentials as a Nigerian-British artist (as opposed to a francophone African artist connected to France via colonial history and contemporary ‘Eurafrican’ geo-politics) have meant that his diasporan status as African and a Westerner does nothing to ‘deterritorialize’ him from being the marginal ‘Other’ in accordance with the MQB’s somewhat fixed and limited categorisation and construction of the Western ‘Self’ as a centralised white male body.

The head of the in-house curatorial team at MQB, Germain Viatte, acknowledges that Yinka Shonibare’s installation was designed to specifically emphasise the ‘paradox of otherness’ (Viatte, 2007: 7), and notes that the artist himself embodies this as both an insider and an outsider within the context of the European museum space. It is Viatte who acknowledges Shonibare’s family background as the son of a lawyer, and an artist educated at two of Britain’s most elite fine art colleges, that make him typical as an aesthete and arts professional in Western Europe, whilst his Yoruba heritage, and thus his blackness, also make him (in Viatte’s words) ‘for whites – irrevocably “other”’ (Viatte, 2007: 8).

Lastly, Garden of Love was not the first of Shonibare’s art installations to reference 18th century French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard and focus on the pre-revolutionary French aristocracy’s lifestyle of conspicuous wealth, manufactured beauty, and opulence. His contemporary installation ‘The Swing (after Fragonard)’ (2001), which was purchased by the Tate for its permanent collection, is also evocative of this period. In it Shonibare replicates Fragonard’s scene of a woman on a swing being observed by a male suitor from below, with her petticoats fluttering up in the breeze – titled The Swing (c. 1767) whilst currently on display at the Wallace Collection in London [3].

Critics suggest that Shonibare first selected Fragonard for this piece because he captures perfectly the moment of French nobility’s unforeseen demise, by symbolically depicting it as the self-absorbed behaviour of a pair of lovers concerned only with frivolities, and oblivious to the wider political tension gathering around them. The headlessness of the mannequins, once again, appears to reference the use of the guillotine during the French Revolution, but also the anonymity of each featured body, making each one representative of a much wider collective of historical actants. However, whilst all this artistic Anglo-French cross-referencing was (and is) fully apparent to the many museologists and art historians paid to develop and publish their professional, trans-national perspectives on artists and their oeuvres, the collecting practices of museums and galleries, and the commissioning habits of their directors and curators, many members of the public remain unaware of such international contexts and dialogical cross-currents. For this reason, when Garden of Love was exhibited in 2007 it proved to be a confusing exhibition for a number of MQB’s emerging audiences (yet still ‘traditional’ in the sense of being typically representative of museum audience demographics in France), as identified by Bernard Müller through his extensive evaluation of the written audience feedback in exhibition visitors’ comments books. In many cases respondents noted surprise about the contemporary installation piece being displayed in a space openly dedicated to the ‘First Arts’ and, in one case, actually made reference to the commission as ‘sacrilege’. As Müller concluded, perhaps the reality was that many visitors were simply unused to – and, perhaps still, not quite yet ready for – the ‘Other’ (i.e. in the form of Shonibare) ‘speaking back’ to them via such a powerful communication tool as his politically and historically layered artistic installation:

And now the “other” speaks directly to the visitor, by means of this great communication device that is the artistic installation … Yoruba speaks showing he knows our culture as well, if not better than we know our own. Behold, Yinka Shonibare inverts the rules of the game turning into a specialist in the West. (Müller, 2007b: para. 36)

REFERENCES

BADINELLA, C. & CHONG, D. 2013. Contemporary Afro and two-sidedness: Black diaspora aesthetic practices and the art market. Culture and Organization, 1-29.

DABYDEEN, D. 1987. Hogarth’s blacks : images of blacks in eighteenth century English art, Manchester, Manchester University Press.

ENWEZOR, O. 2001a. ‘Elsewhere’. A conversation with Thelma Golden. Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art, 2001, 26-33.

ENWEZOR, O. 2001b. Tricking the mind: the work of Yinka Shonibare. Authentic, ex-centric: conceptualism in contemporary African art., 214-229.

FINERTY, K. 2011. Who, what, wear: where style meets substance. Studio Museum in Harlem: Studio Blog: Features – http://www.studiomuseum.org/studio-blog/features

MILLER, M. L. 2009. Slaves to fashion [electronic resource] : black dandyism and the styling of black diasporic identity, Durham, Duke University Press.

MÜLLER, B. 2007a. Entretien avec Yinka Shonibare MBE [Interview with Yinka Shonibare MBE]. In: VIATTE, G. (ed.) Yinka Shonibare, MBE: Jardin d’amour: catalogue de l’exposition [Garden of love: exhibition catalogue]. Paris: Flammarion.

MÜLLER, B. 2007b. Le « Jardin d’Amour » de Yinka Shonibare au musée du quai Branly ou: quand l’« autre » s’y met [The “Garden of Love” by Yinka Shonibare at the Quai Branly Museum or: when the “other” gets going]. CeROArt : Conservation, Exposition, Restauration d’Objets d’Art – http://ceroart.revues.org/386

SMALLS, J. 2003. “Race” as spectacle in late-nineteenth-century French art and popular culture. French Historical Studies, 26, 351-382.

VIATTE, G. 2007. Yinka Shonibare, MBE: Jardin d’amour: catalogue de l’exposition [Garden of love: exhibition catalogue], Paris, Flammarion.

WAJID, S. 2007. Yinka Shonibare at the Musée du Quai Branly [Review]. Darkmatter [Online]. Available: http://www.darkmatter101.org/site/2007/05/06/yinka-shonibare-at-the-musee-de-quai-branly/.

NOTES

[1] The Musée du Quai Branly (MQB) opened in Paris in 2006 with the stated intention of celebrating the arts of Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas. The original impetus to create the museum came from former French President Jacques Chirac who – following a tradition of heads of state securing their political legacies by commissioning major cultural projects, known collectively as ‘les grands travaux’ – wanted to emulate predecessors such as Georges Pompidou and François Mitterand by building a major architectural and cultural landmark in Paris.

[2] Wajid’s comments allude to criticism of Euro-American museums and galleries more broadly, also highlighting that the granting of an occasional commission to one or two prominent black artists of African descent is insufficient to counterbalance the ongoing and systemic absence of workforce diversity as regards the employment of diasporean African, Asian and Caribbean museum and gallery professionals born in Europe.

[3] The full title of Fragonard’s The Swing is ‘Les hasards heureux de l’escarpolette’ [‘The Happy Accidents of the Swing’] (c. 1767).

One response to “Yinka Shonibare MBE’s ‘Jardin d’Amour’ [Garden of Love] (Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, 2007)”

An excellent , informative well -researched piece. Saw the painting from a more nuanced perspective

LikeLike